(Originally submitted as coursework towards my Masters in Global Public Health at the University of Manchester)

Access to safe abortion services is a neglected issue in sexual and reproductive health worldwide. In 2008, more than 70,000 women died from complications related to unsafe abortions globally, whilst unsafe abortions account for 13% of all maternal mortality (WHO, 2012, A). In some regions such as sub-Saharan Africa, this figure can be as high as 520 deaths per 100,000 (Say et al, 2014). One third of all abortions worldwide between 2010 and 2014 were carried out in unsafe contexts, and 97% of unsafe abortions occurred in Lower and Middle Income countries (LAMICs).

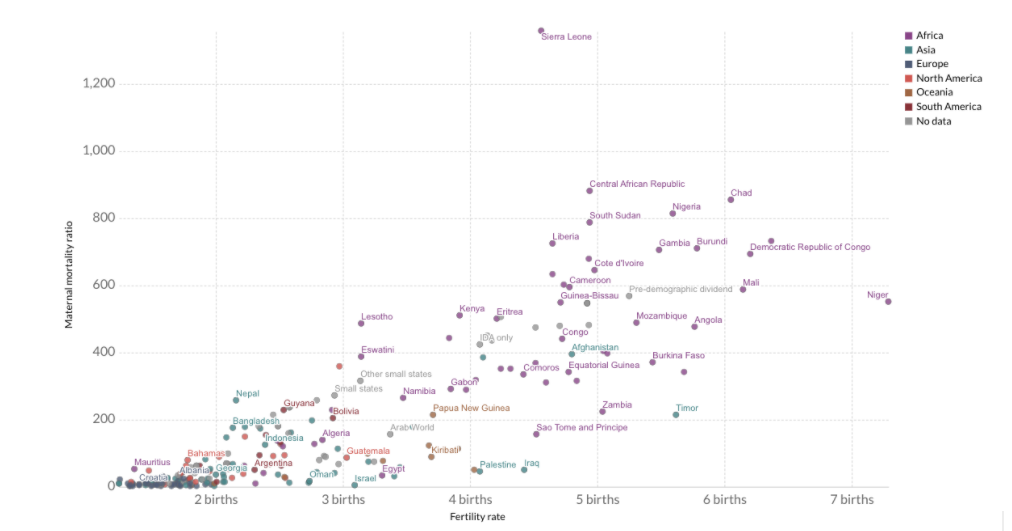

Chart 1. Maternal mortality vs fertility rate by country, 2015. (Our World In Data, 2015)

Whilst total abortion rates are similar between countries with highly restrictive abortion regulations and those where abortion is permitted (Vogelstein and Turkington, 2019), the proportion of unsafe abortions is significantly higher in states that impose more restrictive abortion laws than in states with less restrictive abortion laws (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2014, Ganatra et al, 2017). Additionally, as chart 1 shows, women suffer significantly higher maternal mortality as fertility rate increases, whilst removing restrictions to accessing abortion services reduces maternal mortality (WHO, 2012, B)

In Sierra Leone, where abortion is still illegal, around 1 in 75 pregnancies result in the death of the mother (Our World in Data, 2015). Laws legalising abortion were blocked by the President, Bai Koroma, in 2016 after protests by religious leaders, despite the bill being passed by MPs (BBC, 2016) and there remains a significant cultural pressure to restrict access to abortion in Sierra Leone and many other countries around the world.

Where abortion is restricted, survey data shows that the wanted fertility rate is on average 1 child lower than the actual fertility rate (Our World In Data, 2016), demonstrating a clear need and desire for improved access to reproductive and sexual health services to avoid unwanted pregnancies.

Evidence also shows a correlation between the number of children a woman has and a reduction in earning potential, through an inability to work whilst children are young, and a subsequent lowering in earnings upon returning to work (Lundborg et al, 2017). Permissive abortion laws are also shown to increase female labor force participation via a decrease in fertility rate (Bloom et al, 2009). The ability to choose whether to carry a pregnancy to term therefore impacts a woman’s right to work and to equal pay under Article 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (United Nations, 1948). Further rights, such as the right to an education, are impacted where young mothers are prevented from attending school as a result of childcare responsibilities.

Whilst access to abortion improves access to education, education itself also influences the rates of abortion. In countries where abortion is legal and safe, a higher level of education is generally correlated with a lower frequency of abortion (Eskildet al, 2007) and a lower fertility rate (Leon, 2004), alongside an increased support for relaxed (“pro-choice”) abortion laws (Jelen and Wilcox, 2003).

Human Rights and Abortion

A lack of access to family planning, contraception, and safe abortion services can be shown to impact womens’ rights in many ways, including the essential right to bodily autonomy and integrity and the ability to take paid employment and participate in cultural activities (Tzvetkova and Ortiz-Espina, 2017).

Article 27 of the UDHR states that everyone has the right to share in scientific advancement and its benefits. Safe pharmaceutical abortion practices have been available since 1988 (Baulieu & Rosenblum, 1991) and yet many abortions are carried out in unsafe contexts not because safe abortions are illegal, but because they are unavailable (Chemlal and Russo, 2019).

The right to life and the right to health are enshrined in the UDHR and the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) alongside more specific treaties such as the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). CEDAW affirms the right of all women “to decide freely and responsibly on the number and spacing of their children and to have access to the information, education and means to enable them to exercise these rights” (UN General Assembly, 1979). “There can be no right to health without the right to access safe abortion” (Priyanka, 2019, pp. 2359).

However, despite this apparent consensus that access to safe abortion services should be an essential human right, in practice, access is still restricted.

Restricted Access to Abortion

The reasons for restricting access to abortion are often cultural or religious. Followers of many religions believe that abortion is morally wrong, often due to an assertion that a foetus is “alive” from the point of conception. Most abortion legislation recognises the difficult ethical compromise between the rights of women and the rights of an unborn child, usually differentiating between early and late-term abortions, with the cut-off around 12 weeks of pregnancy, beyond which abortion is only permitted if the mother’s life is at risk (Center for Reproductive Rights, 2021).

Strict abortion laws aim to reduce the number of abortions by restricting access to cases only where the mother’s life is at risk or banning the procedure entirely. However, this often has the unintended consequence that women will travel to seek abortions elsewhere or access illegal and unsafe abortion services (Barr-Walker et al, 2019; Jerman et al, 2017).

Example: Northern Ireland

In the UK, abortion was decriminalised by the Abortion Act of 1967. However, due to conservative and religious pressure, an exemption to the 1967 Act was made for Northern Ireland (Jelen et al, 1993), and abortion remained illegal there until 2019. Women who wanted an abortion were forced to travel to England or self-manage a medical abortion at home, which was both stigmatised and criminalised (Aiken et al, 2018).

This situation was widely considered unacceptable on a human-rights basis, and a UN expert committee declared that the UK was in violation of women’s human rights through restricting access to safe abortion: “The situation in Northern Ireland constitutes violence against women that may amount to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment,” stated CEDAW Vice-Chair Ruth Halperin-Kaddari (OHCHR, 2018).

In June 2018, in a case brought by Sarah Ewart against the Northern Ireland Executive, the UK Supreme Court concluded that “the current law in Northern Ireland breaches human rights, in particular women and girls’ right to private and family life under Article 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights” (NIHRC, 2019). The UK government subsequently clarified that the Northern Ireland Executive must make CEDAW-compliant changes to regulations to ensure that women seeking an abortion do not have to travel to England (House of Commons, 2019).

Despite the UN declaration, the Supreme Court ruling, and clarification by Westminster, there is considered to be a cultural reluctance in Northern Ireland to fulfil the obligations placed upon the Department of Health (Gallen, 2020). Abortion services, despite being legal, remain sparse and many women seeking abortions must still travel to England.

Example: The USA

During the 1960s, a number of US states began to decriminalise abortion under certain circumstances, such as cases of rape, incest, or if pregnancy could lead to permanent physical impairment of the mother (Kliff, 2013). Other states followed suit, and Washington and Hawaii passed laws allowing elective abortions. In 1973, the Supreme Court in Roe v. Wade declared all laws in the USA prohibiting abortion to be invalidated, and set guidelines for the availability of safe abortion services up to 12 weeks gestation. The court made this decision based upon the rights implied in the 14th Amendment of the Constitution of the United States of America: “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property…” (US Const. amend. XIV, sec. 1). The human rights in the US constitution were sufficent to change the laws of 30 states where abortion was previously illigal, and normalise laws in 20 further states.

Despite this, an anti-abortion stance persists in parts of the US and has shaped abortion policy. Just three years after Roe v. Wade, The United States Congress passed the “Hyde Amendment”. This amendment, introduced by conservative Congressman Henry J. Hyde, bars the use of federal funds (not state funds) to pay for abortion services except when the life of the mother would be endangered by carrying the pregnancy to term (ACLU, 2021). Implementation of the Hyde Amendment was blocked for some time by pro-choice organisations but was eventually passed in 1977.

The Hyde Amendment violates CEDAW by restricting access to essential reproductive and sexual health services (RHS), and availability of abortion services in the US remains limited by a reluctance to recognise the fundamental rights of women to “decide freely and responsibly on the number and spacing of their children and to have access to the information, education and means to enable them to exercise these rights,” (CEDAW, Art. 16, e). The implementation of CEDAW in the U.S. “would radically change the basic equality rights of American women, including the right to an abortion.” (Benshoof, 2011. pp.105). However, the USA has to date refused to ratify CEDAW at federal level, though several US cities, counties and states have adopted the principles of CEDAW in local laws (Pierson, 2018).

This anti-abortion stance spreads beyond the US via mechanisms such as the “Global Gag Rule” or the “Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance” policy. This policy bans foreign NGOs that receive US Government funds from using funds from any source to provide abortion services, counselling or advocate for progressive abortion laws. President Trump expanded this in 2017 to include funds through the “President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief” (PEPFAR). PEPFAR constitutes nearly $9billion in funding and meant NGOs had to choose between complying with the rules and denying access to safe abortion, or losing funding (Priyanka, 2019).

The impact of such policies increases unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions in LAMICs via two mechanisms: it makes it harder to access safe abortion services provided by NGOs, and it impacts the funding of NGOs providing reproductive and sexual health services, reducing access to contraception (Mavodza et al, 2019).

However, under President Biden, there appear to be moves towards a rights-based approach. On January 28, 2021, he rescinded the Mexico City Policy, as part of “the administration’s plan to protect the rights of women both domestically and abroad” (Brennan, 2021). Foreign NGOs can now obtain PEPFAR and family planning funding whilst offering safe abortion services and counselling.

Example: Organisation of African Unity

In 1995, the OAU (Organisation of African Unity) Assembly, consisting of the heads of state of all 54 African member states, mandated the creation of a protocol to recognise and enshrine womens’ rights. The process took many years, but after lobbying by NGOs, the finished Protocol To The African Charter On Human And Peoples’ Rights On The Rights Of Women In Africa, better known as the Maputo Protocol, was adopted by the African Union in 2003.

Article 14 of The Maputo Protocol explicitly defines access to safe abortion as a human right in cases of “sexual assault, rape, incest, and where the continued pregnancy endangers the mental and physical health of the mother or the life of the mother or the foetus” (African Union Maputo Protocol, 2003. Art. 14, 2, c) and additionally states that women’s reproductive rights are “inalienable, interdependent and indivisible” human rights.

Many African countries expressed reservations about Article 14 which specifically relates to womens’ health and reproductive rights, including Burundi, Senegal, Sudan, Rwanda and Libya (Viljoen, 2009), and the US-based anti-abortion organisation “Human Life International, described it as “a Trojan horse for a radical agenda.” (Vatican Radio, 2008)

Despite the Maputo Protocol, in many areas in Africa, abortion is still highly stigmatised. In many clinical settings, either through personal belief or fear of reprisals for conducting abortions, that despite abortion facilities being present, there are not the clinicians available to perform them (Favier et al, 2018). Thus, whilst the Maputo protocol advanced the rights of women in principle, in practice, governments have not ensured equitable availability of safe abortion services, and there is still a gap between governments recognising and fulfilling their obligations (Albertyn, 2015).

Example: Israel

Abortion was made legal in Israel in 1977 and in 2014, the law was updated to allow for on-demand abortions at no cost to women between 20 and 33 years of age (Kamin, 2014).

However, Israel implemented abortion laws as a result of many years of compromise. Chaika Grossman, one of very few female members of the Israeli Parliament in 1977, avoided any mention of human rights in relation to abortions in order to appease the highly conservative parliament. Instead, legislation was drafted based on “the assumption that such a reform would increase the birthrate among middle-class Jewish women on the one hand, and control the fertility of the less privileged sectors of the community on the other hand.” (Rimalt, 2017, pp. 329).

Thus, despite Israel’s abortion laws being some of the most permissive in the world (Kamin, 2014), this approach leaves them vulnerable to political influence and change. Without a grounding in “inalienable, interdependent and indivisible” human rights, laws drafted by legislators may be changed according to the whim of the government of the time, which leaves the women of Israel vulnerable to abortion services being restricted once again.

Conclusion

It is clear that human rights frameworks and rights-based approaches to access to abortion services:

- Offer a framework for governments to shape policies, programmes, statutes and Protocols, as seen in the Maputo Protocol and by President Biden’s rescinding of the Global Gag Rule.

- Provide clarity for courts to make decisions and turn rights into law, as seen in the USA in Roe v Wade.

- Empower individuals to know, understand, demand and exercise their rights, as exemplified by Sarah Ewart’s actions in Northern Ireland.

- Enable governments to be held accountable when they do not protect those rights, as is ongoing in Africa and Northern Ireland, where women have the right to access abortion but accessibility remains limited.

The increasingly progressive standards codified by human rights frameworks serve to improve access to safe abortion services, through transforming abortion laws, advancing law and policy reforms, and putting in place frameworks that persist despite political change (Fine et al, 2017). Governments that recognise abortion as a human right must do more than make it legal; they are obligated to ensure that safe abortions are available, accessible, acceptable and of appropriate quality.

The cases of the USA, Northern Ireland and Africa demonstrate the power of absolute, and inalienable human rights. Whilst governments change and cultures shift, human rights are immutable. Courts, in their power to define law, can utilise human rights frameworks, such as the UDHR, CEDAW, the Maputo Protocol or the US Constitution to make clear and lasting decisions, including the decision to respect, protect and fulfil the right of every woman to access safe abortion services.

References:

ACLU, 2021. Access Denied: Origins of the Hyde Amendment and Other Restrictions on Public Funding for Abortion. Available at: https://www.aclu.org/other/access-denied-origins-hyde-amendment-and-other-restrictions-public-funding-abortion (Accessed: 21 April 2021).

Aiken, A. et al. 2018. “The impact of Northern Ireland’s abortion laws on women’s abortion decision-making and experiences”, BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health, 45(1), pp. 3-9. doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2018-200198.

Albertyn, C., 2015. Claiming and defending abortion rights in South Africa. Revista Direito GV, 11(2), pp.429-454.

Barr-Walker, J., Jayaweera, R.T., Ramirez, A.M. and Gerdts, C., 2019. Experiences of women who travel for abortion: A mixed methods systematic review. PloS one, 14(4), p.e0209991.

Benshoof, J., 2011. US Ratification of CEDAW: An Opportunity to Radically Reframe the Right to Equality Accorded Women Under the US Constitution. NYU Rev. L. & Soc. Change, 35, p.103.

Baulieu, Etienne-Emile; Rosenblum, Mort, 1991. The “abortion pill” : RU-486, a woman’s choice.

New York: Simon & Schuster.

Brennan, T. 2021. Biden’s decision to rescind the Global Gag Rule could have implications for the US approach to sexual health and reproductive rights at the UN | Universal Rights Group. Available at: https://www.universal-rights.org/universal-rights-group-nyc-2/bidens-decision-to-rescind-the-global-gag-rule-could-have-implications-for-the-us-approach-to-sexual-health-and-reproductive-rights-at-the-un/ (Accessed: 27 April 2021).

BBC News, 12 March 2016. Sierra Leone abortion bill blocked by President Bai Koroma again. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-35793186 (Accessed: 20 April 2021).

Bloom, D.E., Canning, D., Fink, G. and Finlay, J.E., 2009. Fertility, female labor force participation, and the demographic dividend. Journal of Economic growth, 14(2), pp.79-101.

Center for Reproductive Rights. 2021. The World’s Abortion Laws Available at: https://maps.reproductiverights.org/worldabortionlaws (Accessed: 27 April 2021).

Chemlal, S. and Russo, G., 2019. Why do they take the risk? A systematic review of the qualitative literature on informal sector abortions in settings where abortion is legal. BMC women’s health, 19(1), pp.1-11.

Eskild, A., Nesheim, B.I., Busund, B., Vatten, L. and Vangen, S., 2007. Childbearing or induced abortion: the impact of education and ethnic background. Population study of Norwegian and Pakistani women in Oslo, Norway. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica, 86(3), pp.298-303.

Favier, M., Greenberg, J.M. and Stevens, M., 2018. Safe abortion in South Africa:“We have wonderful laws but we don’t have people to implement those laws”. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 143, pp.38-44.

Fine, J.B., Mayall, K. and Sepúlveda, L., 2017. The role of international human rights norms in the liberalization of abortion laws globally. Health and human rights, 19(1), p.69.

Gallen, E. et al. 2020. “Abortion is now legal in Northern Ireland – but why aren’t procedures actually being carried out?”, The Telegraph. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/life/abortion-now-legal-northern-ireland-arent-procedures-actually/ (Accessed: 9 March 2021).

Ganatra, B. et al. 2017 “Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010–14: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model”, The Lancet, 390(10110), pp. 2372-2381. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31794-4.

Guttmacher Institute, 2017. Appendix Table 1: Status of the world’s 193 countries and six territories/nonstates, by six abortion-legality categories and three additional legal grounds under which abortion is allowed.

https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_downloads/aww_appendix_table_1.pdf (Accessed: 20 April 2021).

House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee. 2019. “Abortion law in Northern Ireland”. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmwomeq/1584/158408.htm (Accessed: 9 March 2021).

Jelen, T., O’Donnell, J. and Wilcox, C. 1993. “A Contextual Analysis of Catholicism and Abortion Attitudes in Western Europe”, Sociology of Religion, 54(4), p. 375. doi: 10.2307/3711780.

Jelen, T.G. and Wilcox, C., 2003. Causes and consequences of public attitudes toward abortion: A review and research agenda. Political Research Quarterly, 56(4), pp.489-500.

Jerman, J., Frohwirth, L., Kavanaugh, M.L. and Blades, N., 2017. Barriers to abortion care and their consequences for patients traveling for services: qualitative findings from two states. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health, 49(2), pp.95-102.

Kamin, D., 2014. Israel’s abortion law now among world’s most liberal. The Times of Israel, 6.

Kavaler, T., 2021. Israel’s abortion rate continues 32-year decline. Jerusalem Post. Available at: https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/israels-abortion-rate-continues-32-year-decline-654367 (Accessed: 27 April 2021).

Kliff, S., 2013. Charts: How Roe v. Wade changed abortion rights. The Washington Post, 22.

Leon, A., 2004. The effect of education on fertility: evidence from compulsory schooling laws. unpublished paper, University of Pittsburgh.

Lee, E., Ingham, R., 2004. A matter of choice?: exploring reasons for variations in the proportion of under-18 conceptions that are terminated. Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York.

Lundborg, P., Plug, E. and Rasmussen, A.W., 2017. Can women have children and a career? IV evidence from IVF treatments. American Economic Review, 107(6), pp.1611-37.

Mavodza, C., Goldman, R. and Cooper, B., 2019. The impacts of the global gag rule on global health: a scoping review. Global health research and policy, 4(1), pp.1-21.

NI Human Rights Commission (NIHRC), 2019. Human Rights Commission welcomes Sarah Ewart Judgment. Available at: https://nihrc.org/news/detail/human-rights-commission-welcomes-sarah-ewart-judgment (Accessed: 9 March 2021).

OHCHR. 2018 | UK violates women’s rights in Northern Ireland by unduly restricting access to abortion – UN experts. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=22693&LangID=E (Accessed: 21 April 2021).

Our World In Data, 2015. Maternal mortality ratio vs. Fertility rate. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/maternal-mortality-vs-fertility (Accessed: 20 April 2021).

Our World In Data. 2016. Fertility vs wanted fertility. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/fertility-vs-wanted-fertility (Accessed: 20 April 2021).

Pierson, J., 2018. Why the US Needs CEDAW: Abortion as a Human Right in the United States – Global Justice Center, Globaljusticecenter.net. Available at: https://globaljusticecenter.net/blog/1001-why-the-us-needs-cedaw-abortion-as-a-human-right-in-the-united-states (Accessed: 21 April 2021).

Priyanka, P., 2019. The devastating impact of Trump’s global gag rule. The Lancet. 390: 2359

Say, L., Chou, D., Gemmill, A., Tunçalp, Ö., Moller, A.B., Daniels, J., Gülmezoglu, A.M., Temmerman, M. and Alkema, L., 2014. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. The Lancet global health, 2(6), pp.e323-e333.

The US Constitution. 1795: Amendments 11-27. Available at: https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/amendments-11-27 (Accessed: 21 April 2021).

Tzvetkova, S. and Ortiz-Ospina, E., 2017. Working women: What determines female labor force participation. Our World in Data.

United Nations, 1948. Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

United Nations General Assembly, 1979. Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cedaw.aspx (Accessed: 20 April 2021).

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2014. Abortion Policies and Reproductive Health around the World (United Nations publication, Sales No. E. 14. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/policy/AbortionPoliciesReproductiveHealth.pdf (Accessed: 27 April 2021).

Viljoen, F., 2009. An Introduction to the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa. Wash. & Lee J. Civil Rts. & Soc. Just., 16, p.11.

Vogelstein, R. B., Turkington,R. 2019. Abortion Law: Global Comparisons. Council on Foreign Relations. Available at: https://www.cfr.org/article/abortion-law-global-comparisons (Accessed: 27 April 2021).

World Health Organization, 2012 (A). Unsafe abortion incidence and mortality: global and regional levels in 2008 and trends during 1990-2008 (No. WHO/RHR/12.01). World Health Organization.

World Health Organization, 2012 (B). Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems. World Health Organization. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70914/9789241548434_eng.pdf%3Bjsessionid=32652906622D015D8FA4E4DEE2E52BF7?sequence=1 (Accessed: 27 April 2021).