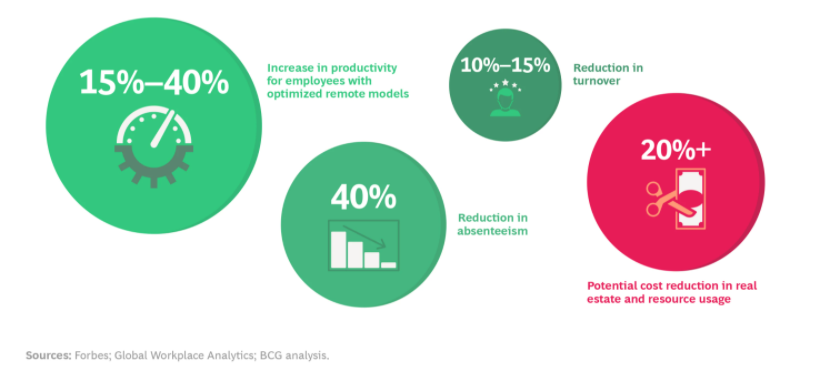

Remote working improves productivity.

Even way back in 2014, evidence showed that remote working enables employees to be more productive and take fewer sick days, and saves money for the organisation. The rabbit is out of the hat: remote working works, and it has obvious benefits.

More and more organisations are adopting remote-first or fully remote practices, such as Zapier:

“It’s a better way to work. It allows us to hire smart people no matter where in the world, and it gives those people hours back in their day to spend with friends and family. We save money on office space and all the hassles that comes with that. A lot of people are more productive in remote setting, though it does require some more discipline too.”

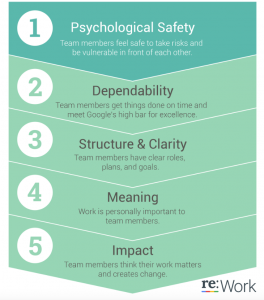

We know, through empirical studies and longitudinal evidence such as Google’s Project Aristotle that colocation of teams is not a factor in driving performance. Remote teams perform as well as, if not better than colocated teams, if provided with appropriate tools and leadership.

Teams that are already used to more flexible, lightweight or agile approaches adapt adapt to a high performing and fully remote model even more easily than traditional teams.

The opportunity to work remotely, more flexibly, and save on time spent commuting helps to improve the lives of people with caring, parenting or other commitments too. Whilst some parents are undoubtedly keen to get into the office and away from the distractions of home schooling, the ability to choose remote and more flexible work patterns is a game changer for some, and many are actually considering refusing to go back to the old ways.

What works for some, doesn’t work for others, and it will change for all of us over time, as our circumstances change. But having that choice is critical.

However, remote working is still (even now in 2020 with the effects of Covid and lockdowns) something that is “allowed” by an organisation and provided to the people that work there as a benefit.

Remote working is now an expectation.

What we are seeing now is that, for employees at least, particularly in technology, design, and other knowledge-economy roles, remote working is no longer a treat, or benefit – just like holiday pay and lunch breaks, it’s an expectation.

Organisations that adopt and encourage remote working are able to recruit across a wider catchment area, unimpeded by geography, though still somewhat limited by timezones – because we also know that synchronous communication is important.

Remote work is also good for the economy, and for equality across geographies. Remote work is closing the wage gap between areas of the US and will likely have the same effect on the North-South divide in the UK. This means London firms can recruit top talent outside the South-East, and people in typically less affluent areas can find well paying work without moving away.

But that view isn’t shared by many organisations.

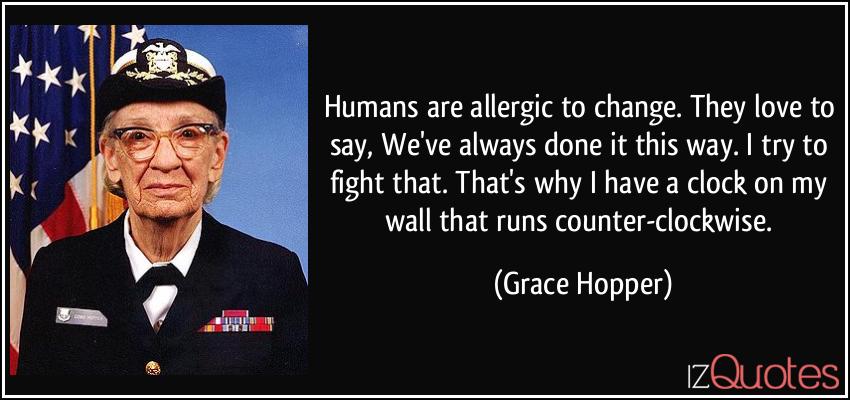

However, whilst employees are increasingly seeing remote working as an expectation rather than a benefit, many organisations, via pressure from command-control managers, difficulties in onboarding, process-oriented HR teams, or simply the most dangerous phrase in the English language: because “we’ve always done it this way“, possess a desire to bring employees back into the office, where they can see them.

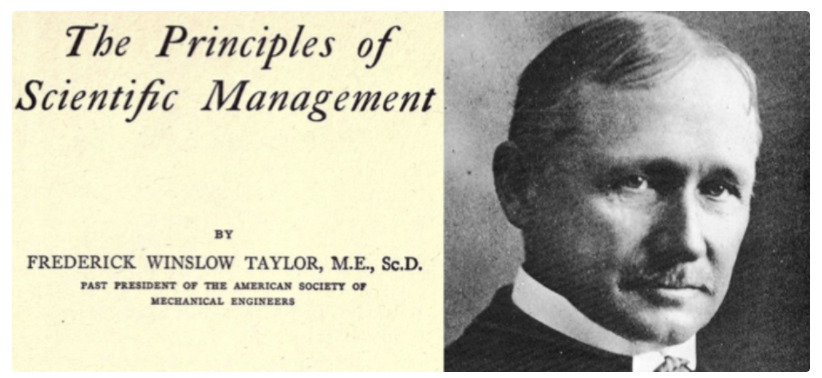

Indeed, often by the managers of that organisation, remote working may be seen as an exclusive benefit and an opportunity to slack off. The Taylorist approach to management is still going strong, it appears.

People are adopting remote faster than organisations.

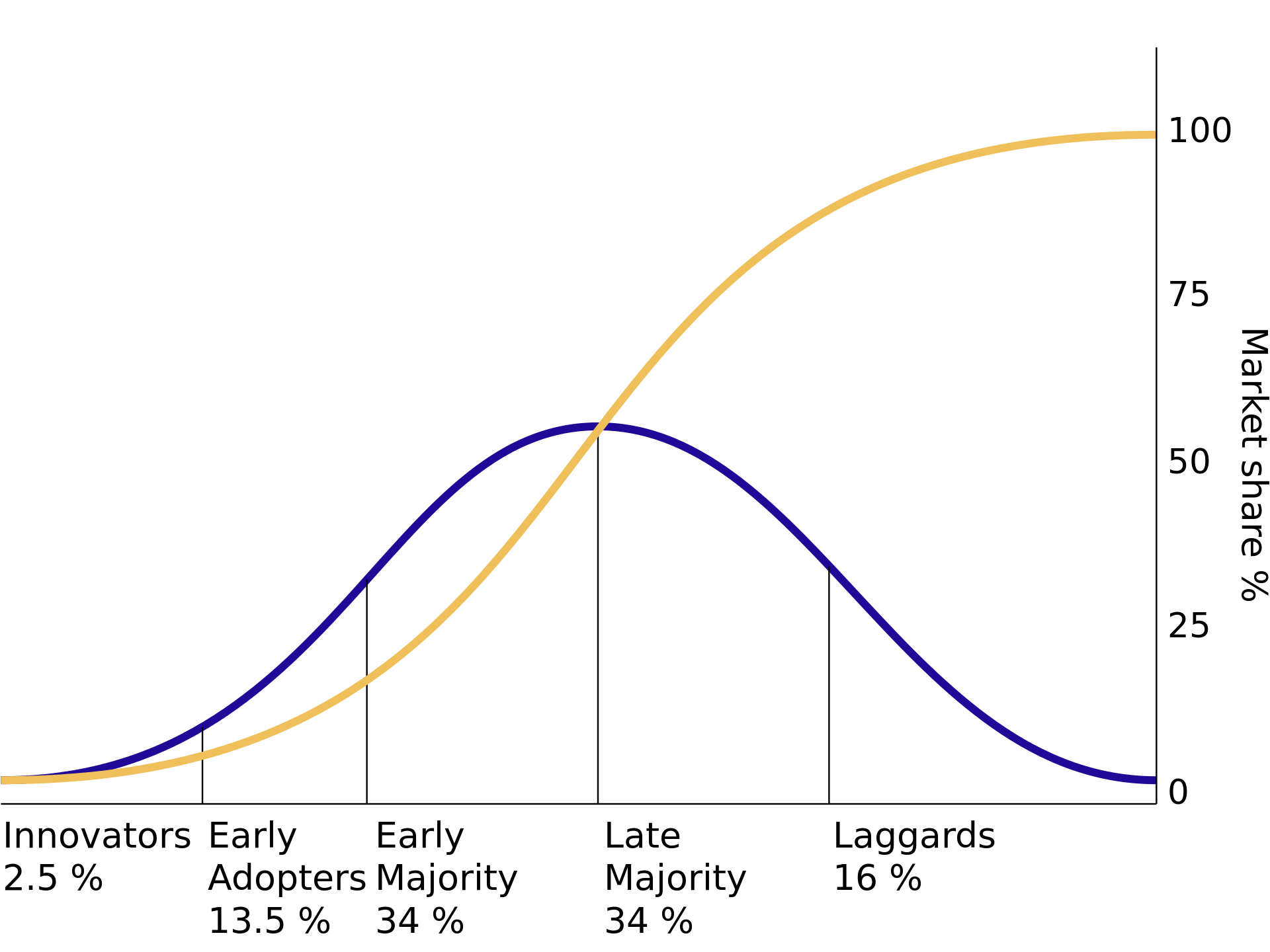

In 1962, Everett Rogers came up with the principle he called “Diffusion of innovation“.

It describes the adoption of new ideas and products over time as a bell curve, and categorises groups of people along its length as innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. Spawned in the days of rapidly advancing agricultural technology, it was easy (and interesting) to study the adoption of new technologies such as hybrid seeds, equipment and methods.

Some organisations are even suggesting that remote workers could be paid less, since they no longer pay for their commute (in terms of costs and in time), but I believe the converse may become true – that firms who request regular attendance at the office will need to pay more to make up for it. As an employee, how much do you value your free time?

It seems that many people are further along Rogers’ adoption curve than the organisations they work for.

There are benefits of being in the office.

Of course, it’s important to recognise that there are benefits of being colocated in an office environment. Some types of work simply don’t suit it. Some people don’t have a suitable home environment to work from. Sometimes people need to work on a physical product or collaborate and use tools and equipment in person. Much of the time, people just want to be in the same room as their colleagues – what Tom Cheesewright calls “The unbeatable bandwidth of being there.”

But is that benefit worth the cost? An average commute is 59 minutes, which totals nearly 40 hours per month, per employee. For a team of twenty people, is 800 hours per month worth the benefit of being colocated? What would you pay to obtain an extra 800 hours of time for your team in a single month?

The question is one of motivation: are we empowering our team members to choose where they want to work and how they best provide value, or are we to revert to the Taylorist principles where “the manager knows best”? In Taylors words: “All we want of them is to obey the orders we give them, do what we say, and do it quick.”

We must use this as a learning opportunity.

Whilst 2020 has been a massive challenge for all of us, it’s also taught us a great deal, about change, about people and about the future of work. The worst thing that companies can do is ignore what they have learned about their workforce and how they like to operate. We must not mindlessly drift back to the old ways.

We know that remote working is more productive, but there are many shades of remoteness, and it takes strong leadership, management effort, good tools, and effective, high-cadence communication to really do it well.

There is no need for a binary choice: there is no one-size-fits-all for office-based or remote work. There are infinite operating models available to us, and the best we can do to prepare for the future of work is simply to be endlessly adaptable.