(Originally submitted as coursework towards my Masters in Global Public Health at the University of Manchester)

This discussion focuses on strengthening health system service delivery and accessibility in Mexico, via the “Oportunidades” programme. The Oportunidades programme is a useful one to explore, firstly because its horizontal approach “has led to increased health service utilization” (Blas et al p.155, 2011) and improved school attendance and nutrition of children across Mexico. Secondly, it has wider applications, as over 50 countries have since replicated the Oportunidades model (Lamanna, 2014).

Oportunidades has also been known as “Progresa” and “Prospera”, but for the purpose of this discussion, “Oportunidades” will be used throughout.

Context

Mexico is a Lower and Middle-Income Country (LAMIC) with high degrees of social inequality. It encapsulates many of the challenges experienced by countries of all income levels (Frenk, 2006). Poor children in Mexico are more exposed to health risks and hazards than their wealthier counterparts and have less resistance to disease due to undernutrition; reduced access to healthcare further compounds this inequity (Victora et al, 2003). A commitment to Universal Healthcare (UHC) is embedded within the constitution of Mexico, and was achieved in 2012 via a national health insurance programme called Seguro Popular (Knaul et al, 2012), alongside universal education, shelter and social security (Lárraga, 2016).

As such, Mexico is an excellent candidate for research into strengthening health systems, particularly through a Social Determinants of Health (SDH) lens. Under the direction of Julio Frenk, Health Minister 2000-2006, SDH and evidence-based approaches were used to develop policies which focused on equity and quality (Lancet, 2004).

The health system in Mexico is a hybrid model of publicly and privately financed and delivered healthcare and is segmented via three categories: salaried and retired citizens, self-employed or unemployed workers, and those with the ability to pay (Frenk and Gomez-Dantes, 2016).

Health System Service Delivery Improvement

Founded in 1997, Oportunidades is a conditional cash transfer (CCT) programme, funded through general taxation. Unlike vertical, selective interventions, Oportunidades takes a horizontal approach. This reflects the Alma-Ata statement that realising ‘Health For All’, “requires the action of many other social and economic sectors in addition to the health sector” (WHO, 1978, I). It is intended to lift families out of cycles of poverty through combined healthcare, nutrition and education approaches, which aligns with the first five Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly, of No Poverty, Zero Hunger, Good Health and Well-being, Quality Education and Gender Equality.

The programme is centrally administered and initially covered 300,000 families across 12 states with a budget of 58.8 million USD (Levy, 2006). By 2006, the programme covered 5 million families across 32 states (Bautista Arredondo et al, 2008). The programme now covers over 6.4 million families, alongside training programmes to boost employment, and programmes to support the elderly (Sedesol, 2012).

Conditional payments are made directly from the government to the primary caregiver (usually the mother) of eligible children if they meet requirements, such as school attendance, registering with health clinics, accepting preventative healthcare, attending prenatal and postnatal clinics, and visiting nutrition clinics (Gertler, 2000). The money goes into beneficiaries’ banks accounts or onto prepaid debit cards and consists of contributions for nutrition, health and education, alongside food supplements. This incentivises the uptake of health system services while giving families autonomy over how they spend payments.

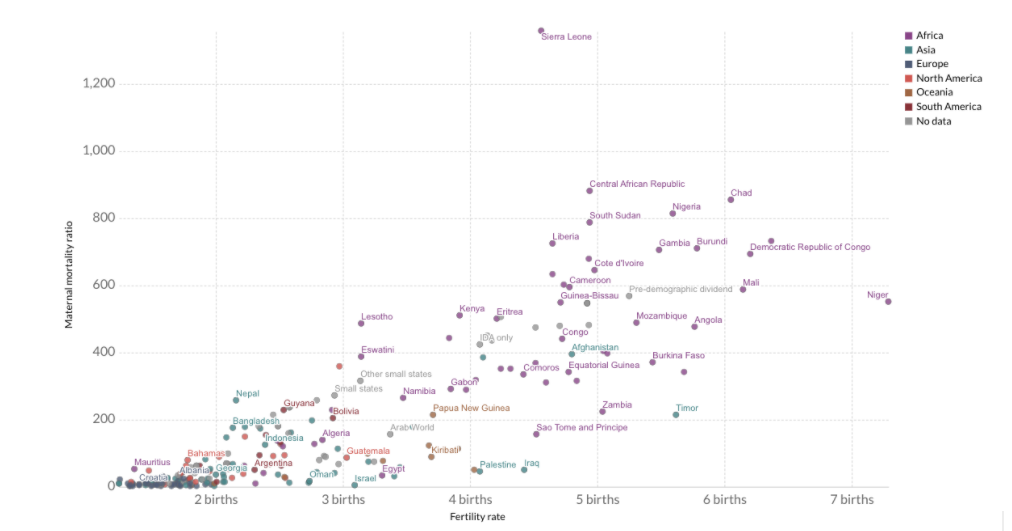

Crucially, education is integrated into Oportunidades – the strong universal correlation between education and health outcomes is well-established (Holmes and Zajacova, 2014). The programme further demonstrates its SDH credentials and alignment with the goal of Gender Equality, by providing larger incentives for girls to remain in school (Darney et al, 2014). Girls’ education is closely linked to health outcomes; women with higher levels of education have fewer children (Darney et al, 2014), experience fewer childbirth complications because they are more likely to seek medical assistance (Mainuddin et al, 2015), and have greater employment opportunities which help break the intergenerational cycle for families in poverty. Over medium and longer terms, this reduces the burden on health system service delivery.

Operational and strategic strengths

One of the programme’s strengths is that two of its key functions facilitate a robust evaluation and improvement feedback loop. Firstly, the well-defined target populations and sequential rollout aids in assessing effectiveness and provides researchers with a Randomised Control Trial (RCT) model (Ambroz and Shotland, 2013) which can compare treatment group families with control group families in locations not yet covered by Oportunidades. Secondly, information collected before payments begin is compared with later results, to establish longitudinal data about the intervention effectiveness (Skoufias, 2005). This has allowed service delivery improvements to be evidence-informed and targeted.

For example, continuous evaluation and improvement has enabled controlled scaling of the programme. Initially, only families that fell below an “extreme poverty” line in rural areas with schools and healthcare facilities within five kilometres were targeted (Ordóñez-Barba, 2019). Using evidence-based decisions, the criteria have since been revised to include urban families above the extreme poverty line (Lárraga, 2016).

Another strength is that the programme’s Operational Monitoring Model (MSO) combines national oversight with empowered, autonomous local delivery, which enables rapid response to feedback and systemic changes to service delivery. In 2010, mobile devices were introduced to carry out the ENCASEH (Socio-Economic and Demographic Characteristics of Households) eligibility survey. This increased the pace of eligibility interviews, and allowed staff to inform beneficiaries of their eligibility immediately. However, after staff reported negative reactions to delivering news of ineligibility, including having mobile devices destroyed or stolen and individuals refusing to let them leave, this was quickly changed to ensure that families were not informed until staff had left (Lárraga, 2016).

Through the MSO, an Operational Monitoring Report is produced every two months, and references 41 key performance indicators organised around themes of “i) enrollment of families; ii) continuity of beneficiaries in the roster; iii) education; iv) health; v) nutrition; vi) certification of co-responsibilities; and vii) payment of cash benefits” (Lárraga, 2016). The short reporting cycle with accurate indicators of performance has allowed for rapid evaluation of programme changes and early identification of issues or trends.

Although the programme strategy is defined nationally, it is coordinated through 32 state offices. Within each state, local organisations are coordinated within zones, and component “microzones” serve local families who are visited regularly by staff. This presence on the ground has facilitated communication with beneficiaries even in remote areas, aiding early problem detection and improving engagement (WHO, 2014).

By making direct payments to families, Oportunidades reduces the potential for corruption and improves financial efficiency. For every $100 allocated to the program, $8.20 is absorbed by administrative costs, compared with equivalent programs such as LICONSA and TORTIVALES where $40 and $14 are absorbed respectively (Coady, 2000). Building on that strength, payments are made to the mother “to guarantee that the spending of these resources would be directed toward buying food for the most vulnerable members” (Skoufias, 2005, p88), thus maximising the return on investment in service delivery.

Another strength of the programme, and one reason it has survived changes of government, is its transparency and lack of political alignment. In election years, there has been little or no mass enrollment, to avoid any suggestion that the incumbent government is “buying” votes of beneficiaries. In 2003, workshops and marketing campaigns adopted the slogan “In Oportunidades we all do our share”, to embed a sense of collective ownership and responsibility for the programme. There is therefore little political profit to be gained from a new government changing the scope of Oportunidades, or halting it altogether.

Success of UHC requires health-care service delivery to be managed efficiently (Sumriddetchkajorn et al, 2019). Financially, Oportunidades has proven to be efficient and stable at scale. Whilst the coverage and the budget of the programme has increased from 0.3million to 6.4million families from 1997 to 2017, the share of the federal expenditure never exceeded 2.3 percent (Ordóñez-Barba and Silva-Hernández, 2019).

Impact on service delivery and access

In respect to service delivery, the impact of Oportunidades is striking. Access to healthcare services has increased: more than 93 percent of beneficiaries in the programme have access to regular medical care, including preventative medicine and treatment (ASF, 2016, in Ordóñez-Barba & Silva-Hernández, 2019), compared to the average of 51.5% across the population (Gutiérrez et al, 2014).

Access to prenatal and postnatal healthcare increased by 12.2% over a ten-year period (Barber & Gertler, 2009). In the programme’s first year, healthcare clinic visit rates grew faster than in control areas, as did immunisation rates and prenatal and postnatal care. The increase in prenatal care also significantly reduced the number of first visits in the second and third trimesters of pregnant women (Gertler, 2000). Maternal and child mortality has improved significantly (Gertler, 2000) and the number of children suffering from malnutrition dropped from 25% to 8.2% between 2000 and 2015, “alongside a greater efficiency in relation to the cost of medical attention” (Ordóñez-Barba & Silva-Hernández, p.97, 2019). A 2004 study on Oportunidades’ impact on growth and anaemia in children, showed that haemoglobin levels were higher in children in treatment groups, and the programme was associated with better growth among the poorest and youngest infants (Rivera et al, 2004).

Participation in Oportunidades also correlates with increased diabetes mellitus detection and treatment (Behrman and Parker, 2011) through improved healthcare access.

Weaknesses in relation to health system service delivery

Oportunidades is not without weaknesses. Errors are prevalent in targeting, to the exclusion of eligible, and inclusion of ineligible, families (Ordóñez-Barba and Silva-Hernández, 2019). Some have critiqued the programme’s RCT methodology, suggesting that a quantitative approach that drives towards binary options of success or failure leaves little room for qualitative debate and nuance (Faulkner, 2014). Another criticism is that “contamination” of the treatment groups could occur through members of control groups immigrating to treatment group locations in an attempt to become eligible (Behrman & Todd, 1999).

The programme has been criticised for perpetuating “family-ism”, and the gender inequality inherent in assuming “the role of mothers in guaranteeing the effectiveness of public investments,” (Barba and Valencia, 2016, in Ordóñez-Barba and Silva-Hernández, 2019, p.86), though the same authors also recognise the programme’s commitment to addressing gender inequality through its potential to transform the traditional roles of women.

Some critics doubt how much impact CCT has on the trajectory of families in areas of low job availability. (Ordonez-Barba & Silva-Hernández, 2019) Likewise, it is of little use sending women to health clinics and children to school if the health clinics and schools are poor (Marmot, 2015; García-Guerra et al, 2019). To realise genuine improvements to health systems, the programme must be closely linked to economic strategy to ensure that it can improve “the productivity of families so that they are able to generate income through their own efforts and diminish their dependency on monetary transfers” (Presidencia de la República, 2014, para. 20).

Finally, some consider CCT programmes authoritarian. Whilst Oportunidades is intended to empower beneficiaries: “development can be seen as a process of expanding the freedoms that people enjoy” (Sen, 1985, p.3), imposing conditions upon payments can be seen as infringing on “freedom and dignity, creating disempowerment and power imbalances between programme providers and beneficiaries” (Scheel et al, 2020, p.718). Therefore, whilst Oportunidades aligns with the Alma Ata principles of “comprehensive healthcare for all” (WHO, 1978, VII, 6), it could be argued that its use of CCT conflicts with its spirit of self-determination.

Conclusions

Through their themes of “dignity, people, planet, partnership, justice, and prosperity for majority” the SDGs align with the WHO definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (Oleribe et al, 2015, Commentary). They therefore provide an appropriate ‘North Star’ for improving health system service delivery.

The Oportunidades programme supports the SDGs, particularly as they reflect the interrelationships and dependencies of escaping poverty through education, equality, economic development, partnerships and strong institutions (UN, 2015). Despite its critics, it has proven highly effective in strengthening health system service delivery and access, through its SDH approach.

Word count: 1999

References:

Ambroz, A and Shotland, M. (2013) Are RCTs (Randomised Controlled Trials) a new approach in evaluation? Better Evaluation. Available at: https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/evaluation_faq/rct_new (Accessed: 13 February 2021).

Barber, S. and Gertler, P. (2008) “Empowering women to obtain high quality care: evidence from an evaluation of Mexico’s conditional cash transfer programme”, Health Policy and Planning, 24(1), pp. 18-25. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn039.

Bautista Arredondo, S, et al. (2009) External Evaluation of Oportunidades 2008, 1997–2007: Ten Years of Intervention in Rural Areas (1997–2007), Vol. II. Mexico City: SEDESOL; 2009. Ten years of Oportunidades in rural areas: Effects on health services utilization and health status. Available at: http://www.oportunidades.gob.mx/EVALUACION/es/wersd53465sdg1/docs/2008/2008_volume_ii.pdf

Behrman, J. R., & Todd, P. E. (1999). Randomness in the Experimental Samples of PROGRESA (Education, Health and Nutrition Program); IFPRI Discussion Paper.

Behrman, J. and Parker, S. (2011) “The Impact of the Progresa/Oportunidades Conditional Cash Transfer Program on Health and Related Outcomes for the Aging in Mexico”, SSRN Electronic Journal. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1941850.

Berwick D. (2004) Lessons from developing nations on improving health care British Medical

Journal 328 (11): 24-9

Blas, E., Sommerfeld, J., Sivasankara Kurup, A., & World Health Organization. (2011). Social determinants approaches to public health: from concept to practice. World Health Organization.

Buffardi, A. L. (2018). Sector-wide or disease-specific? Implications of trends in development assistance for health for the SDG era. Health Policy and Planning, 33(3), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx181

Coady, D.P., (2000) THE APPLICATION OF SOCIAL COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS TO THE EVALUATION OF PROGRESA; FINAL REPORT. International Food Policy Research Institute (No. 600-2016-40137).

Faulkner WN. (2014) A critical analysis of a randomized controlled trial evaluation in Mexico: Norm, mistake or exemplar? Evaluation. 20(2):230-243. doi:10.1177/1356389014528602

Fehling, M., Nelson, B. D., & Venkatapuram, S. (2013). Limitations of the Millennium Development Goals: a literature review. Global public health, 8(10), 1109–1122. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2013.845676

Frenk J. (2006) Bridging the divide: Global lessons from evidence-based health policy in Mexico Lancet (368): 954–961

Frenk, Julio & Gomez-Dantes, Octavio. (2016). Health System in Mexico. Health Care Systems and Policies https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6419-8 Springer, New York, NY

García-Guerra, A., Neufeld, L. M., Bonvecchio Arenas, A., Fernández-Gaxiola, A. C., Mejía-Rodríguez, F., García-Feregrino, R., & Rivera-Dommarco, J. A. (2019). Closing the nutrition impact gap using program impact pathway analyses to inform the need for program modifications in Mexico’s conditional cash transfer program. The Journal of nutrition, 149(Supplement_1), 2281S-2289S.

GAVI CSO Factsheet 5 – gavi-cso.org (2013). Available at: https://sites.google.com/a/gavi-cso.org/gavi-cso-org/gavi-cso-hss-platforms/factsheets (Accessed: 31 January 2021).

Gertler, P., (2000). Final report: The impact of PROGRESA on health. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC, 35.

Gutiérrez, J. P., Garcia-Saiso, S., Dolci, G. F., & Ávila, M. H. (2014). Effective access to health care in Mexico. BMC health services research, 14(1), 1-9.

Haux, R., 2006. Health information systems–past, present, future. International journal of medical informatics, 75(3-4), pp.268-281.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1386505605001590

Holmes, C. and Zajacova, A. (2014) “Education as “the Great Equalizer”: Health Benefits for Black and White Adults”, Social Science Quarterly, p. n/a-n/a. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12092.

IFPRI (2002). PROGRESA: breaking the cycle of poverty. Washington, D.C., International Food Policy Research Institute.

Knaul, F. et al. (2012) “The quest for universal health coverage: achieving social protection for all in Mexico”, The Lancet, 380(9849), pp. 1259-1279. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61068-x.

Lancet. (2004) The Mexico statement: strengthening health systems. 364: 1911-1912

Lárraga, L. G. D. (2016). How does Prospera work?: Best practices in the implementation of conditional cash transfer programs in Latin America and the Caribbean. Inter-American Development Bank.

Levy, S. (2006): Progress Against Poverty: Sustaining Mexico’s Progresa-Oportunidades Program, Washington, D.C., Brookings Institution Press.

Luccisano, L. (2006). The Mexican Oportunidades Program: Questioning the linking of security to conditional social investments for mothers and children. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 31(62), 53-85.

Marmot, M. (2015). The health gap: the challenge of an unequal world. The Lancet, 386(10011), 2442-2444.

Mainuddin, A. K. M., Begum, H. A., Rawal, L. B., Islam, A., & Islam, S. S. (2015). Women empowerment and its relation with health seeking behavior in Bangladesh. Journal of family & reproductive health, 9(2), 65.

Ordóñez-Barba, G., & Silva-Hernández, A. (2019). Progresa-oportunidades-prospera: Transformations, reaches and results of a paradigmatic program against poverty. Papeles de Poblacion, 25(99), 77–112. https://doi.org/10.22185/24487147.2019.99.04

Presidencia de la República, (2014), Decreto por el que se crea la Coordinación Nacional de PROSPERA Programa de Inclusión Social, México. DOF – Diario Oficial de la Federación. Available at: http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5359088&fecha=05/09/2014 (Accessed: 11 February 2021).

Rivera, J. A., Sotres-Alvarez, D., Habicht, J. P., Shamah, T., & Villalpando, S. (2004). Impact of the Mexican program for education, health, and nutrition (Progresa) on rates of growth and anemia in infants and young children: A randomized effectiveness study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291(21), 2563–2570. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.21.2563

Sedesol. (2012). Oportunidades, 15 years of results. www.oportunidades.gob.mx Available at: https://www.heart-resources.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Government-of-Mexico-2012-.pdf (Accessed: 09 February 2021).

Scheel, I., Scheel, A. and Fretheim, A. (2020) “The moral perils of conditional cash transfer programmes and their significance for policy: a meta-ethnography of the ethical debate”, Health Policy and Planning, 35(6), pp. 718-734. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czaa014.

Sen A. (1999) Development as Freedom. New York: Alfred Knopf.

Skoufias E, Davis B, de la Vega S. (1999) Targeting the poor in Mexico: an evaluation of the selection of households for PROGRESA. Discussion Paper Briefs. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI)

Skoufias, E. (2005). PROGRESA and its impacts on the welfare of rural households in Mexico (Vol. 139). Intl Food Policy Res Inst.

Sumriddetchkajorn, K. et al. (2019) “Universal health coverage and primary care, Thailand”, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 97(6), pp. 415-422. doi: 10.2471/blt.18.223693.

United Nations (UN) (2015) Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (Accessed: 13 February 2021).

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2015). The Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3 (Accessed: 6 February 2021).

Victora, C. G., Wagstaff, A., Schellenberg, J. A., Gwatkin, D., Claeson, M., & Habicht, J. P. (2003). Applying an equity lens to child health and mortality: More of the same is not enough. In Lancet (Vol. 362, Issue 9379, pp. 233–241). Elsevier Limited. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13917-7

Walsham, G. (2020) Health information systems in developing countries: some reflections on information for action, Information Technology for Development, 26:1, 194-200, DOI: 10.1080/02681102.2019.1586632 Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02681102.2019.1586632?journalCode=titd20

Lamanna, F. (2014). A model from Mexico for the world. World Bank News, 19. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2014/11/19/un-modelo-de-mexico-para-el-mundo (Accessed: 30 January 2021).

World Health Organization. (1978). Primary health care: report of the International Conference on primary health care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12 September 1978. World Health Organization.

World Health Organization, (2005) Resolution WHA58.33. Sustainable health financing, universal coverage and social health insurance. In: 58 World Health Assembly, Geneva, 16-25 May (2005). Volume1.Resolutions, decisions,Annexes. (WHA58/2005/ REC/1).

World Health Organization, 2007. Everybody’s business–strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action.

World Health Organization. (2010). Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: a Handbook of Indicators and Their Measurement Strategies. In World Health Organization (Vol. 35, Issue 1). www.iniscommunication.com

WHO | Health systems service delivery. Available at: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/delivery/en/ (Accessed: 13 February 2021).

World Health Organisation | Q&As: Health systems (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/topics/health_systems/qa/en/ (Accessed: 31 January 2021).