I get a bit confused every year about who is writing the State of DevOps Report, and how that gets decided, and in the past it’s been Puppet, Google, DORA and others, but this year, 2021, it was definitely Puppet.

[Edit: apparently there are two State of DevOps reports now… I’m staying out of that particular argument though!]

The state of DevOps report each year attempts to synthesise and aggregate the current state of the technology industry across the world in respect to our collective transformation towards delivering value faster and more reliably. Or as Jonathan Smart puts it, “Sooner. Safer, Happier”. The DevOps shift has been in progress for over a decade now, and whilst DevOps was always really about culture, the most recent reports are now emphasising the importance of culture, progressive leadership, inclusion, and diversity more than ever before.

Last year, in 2020, the core findings of the State of DevOps Report focussed on:

- The technology industry in general still had a long way to go and there remained significant areas for improvement across all sectors.

- Internal platforms and platform teams are a key enabler of performance, and more organisations were starting to adopt this approach.

- Adopting a long-term product approach over short-term project-oriented improves performance and facilitates improved adoption of DevOps cultures and practices.

- Lean, automated, and people-oriented change management processes improve velocity and performance over traditional gated approaches.

This year (2021), there are a number of key findings building on previous DevOps reports:

1. Well defined and architected Team Topologies improve flow.

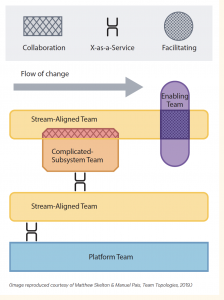

Clear organisational dynamics including well-defined boundaries, responsibilities, and interactions, are critical to achieve fast flow of of value. Whilst last year highlighted the importance of internal platforms, this report emphasises the importance of Conway’s Law, and shows that well defined team structures and interactions, such as platform teams (which scale out the benefits of DevOps transformations across multiple teams), cross-functional value-stream aligned teams, and enabling teams strongly influence the architecture and performance of the technology they build. Team “Interaction Modes” as seen in the diagram below are also critical to define, in the same way that we would define API specifications.

The book Team Topologies expands upon this concept in great detail, and Matthew and Manuel, the authors, also provide excellent training in order to apply these concepts to your contexts.

What is also clear from the State of DevOps Report this, and has been for some time, is that siloing DevOps practices into separate “DevOps teams” is an antipattern to success in most cases. And there should still be no such thing as a “DevOps Engineer”.

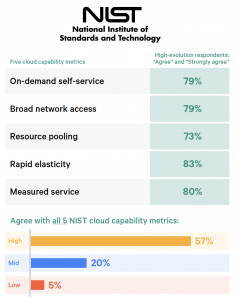

2. Use of cloud technology remains immature in many organisations.

Whilst the majority of organisations are now using cloud technology such as IaaS (infrastructure-as-a-service), most organisations are still using it in ways that are analogous to the ways we used to manage on-premise or datacentre technology. High performers are adopting “cloud-native” technologies and ways of working, including the NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology)essential characteristics of cloud computing: “on-demand self-service, broad network access, resource pooling, rapid elasticity or expansion, and measured service.” How these are implemented is very context-specific, but includes the principles of platform(s) as a product or service, and high competencies in monitoring and alerting and SRE (Site Reliability Engineering) capabilities, whether as SRE teams, or SRE roles in cross-functional teams.

3. Security is shifting left.

High performers in the technology space integrate security requirements early in the value chain, including security stakeholders into the design phase and build phases rather than just at deploy, or even worse, run, phases. Traditional “inspection” approaches to security, governance and compliance significantly impact flow and quality, resulting in higher risk and lower reliability. Applying DevOps principles and practices to include change management, security and compliance improves flow, reliability, performance, and keeps the auditors off your back.

Whilst some call this DevSecOps, many would simply call it DevOps the way it was always intended to be.

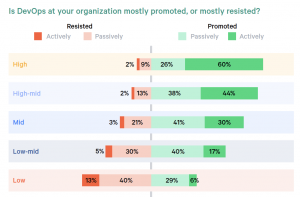

4. DevOps and Digital Transformation must be delivered from the bottom-up, and empowered from the top-down.

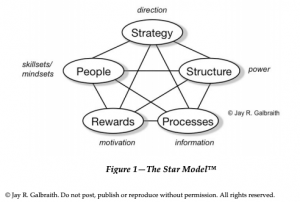

Culture is the reflection of what we do, the behaviours we manifest, the practices we perform, the way we interact and what we believe. Culture change is never successfully implemented only from the top-down, and must be driven and engaged with by those expected to actually change their behaviours and practices.

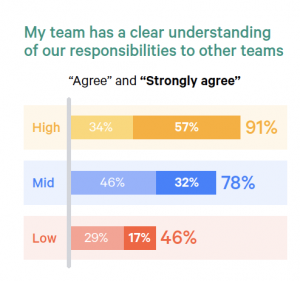

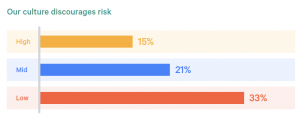

Cultural barriers to change include unclear responsibilities (enter Team Topologies), insufficient feedback loops, fear of change and a low prioritisation for fast flow, and most importantly, a lack of psychological safety.

A lot of these findings, unsurprisingly, echo the findings from Google’s 2013 Project Aristotle, which showed that psychological safety, clarity, dependability, meaning and impact were crucial for high performance in teams.

Extra note on “Legacy” workloads.

The report highlighted the “dragging” effect that legacy workloads can have on flow and change rate, as an effect of their architecture, codebase, or infrastructure, or the fact that nobody in the organisation understands it any longer. Rather than leave alone your legacy workloads, invest in them “so that they’re no longer an inhibitor of progress”. This could be as simple as virtualisation of physical hardware, or decomposing part of the system and moving certain components to cloud-native platforms such as Kubernetes or OpenShift. Even if you have to do something a bit “ugly” such as creating 18GB containers, it’s still a step forward.

TL;DR

- Organisational dynamics must be considered crucial to transformation.

- Cloud-native approaches are critical. It is no good to simply move traditional workloads to the cloud.

- Shift security, compliance and change governance left, and include security stakeholders in all stages of value delivery.

- Culture change is key, and must be promoted from the very “top” as well as delivered from the “bottom”. Psychological safety is at the core of digital and cultural transformations.

If you’re interested in finding out more about DevOps and Digital Transformations, Psychological Safety, or Cloud Native approaches, please get in touch.

Thanks to Nigel Kersten, Kate McCarthy, Michael Stahnke and Caitlyn O’Connell for working on the 2021 State of DevOps Report and providing us with these insights.

View the 2021 Accelerate State of DevOps Report summary here.