[Note: this is now what I call “archival content”. It’s out of date (originally posted in 2017) and I wouldn’t necessarily agree with the content now; particularly in respect to the advent of containerisation. Hopefully it’s still useful though.]

While I was putting together a talk for an introduction to AWS, I was considering how to structure it and thought about the “layers” of cloud technology. I realised that the more time I spend talking about “cloud” technology and how to best exploit it, manage it, develop with it and build business operations using it, the more some of our traditional terminologies and models don’t apply in the same way.

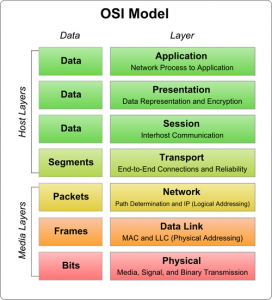

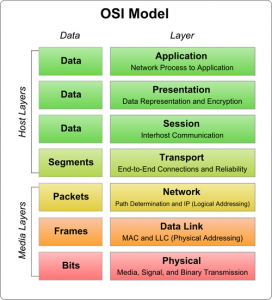

Take the OSI model, for example:

When we’re managing our own datacentres, servers, SANS, switches and firewalls, we need to understand this. We need to know what we’re doing at each layer, who’s responsible for physical connectivity, who manages layer three routing and control, and who has access to the upper layers. We use the terms “layer 3” to describe IP-based routing or “layer 7” to describe functions interacting at a software level, and crucially, we all know what each other means when we use these terms.

With virtualisation, we began to abstract layers 3 and above (layer 2? Maybe?) into software defined networks, but we were still in control of the underlying layers, just a little less “concerned” about them.

Now, with cloud tech such as AWS and Azure, even this doesn’t apply any longer. We have different layers of control and access, and it’s not always helpful to try to use the OSI model terms.

We pay AWS or Azure, or someone else, to manage the dull stuff – the cables, the internet connections, power, cooling, disks, redundancy, and physical security. Everything we see is abstract, virtual, and exists only as code. However, we still possess layers of control and management. We may create multiple AWS accounts to separate environments from each other, we’ll create different VPCs for different applications, multiple subnets for different functions, and instances, services, storage units and more. Then we might hand off access to these to developers and testers, to deploy and test applications.

The point is that it seems we don’t yet have a common language, similar to the OSI model, for cloud architecture. Below is a first stab at what this might be. It’s almost certainly wrong, and certainly can be improved.

Let’s start with layer 1 – the physical infrastructure. This is entirely in the hands of the cloud provider such as AWS. Much of the time, we don’t even know where this is, let alone have any visibility of what it looks like or how it works. This is analogous to layer 1 of the OSI model too, but more complex. It’s the physical machines, cabling, cooling, power and utilities present in the various datacentres used by the cloud providers.

Layer 2 is the hypervisor. The software that allows the underlying hardware to be utilised – this is the abstraction between the true hardware and the virtualised “hardware” that we see. AWS uses Xen, Azure uses a modified Hyper-V, and others use KVM. Again, we don’t have access to this layer, but a GUI or CLI layered on top. For those of us who started our IT careers managing physical machines, then adopted virtualisation, we’ll be familiar with how layer 2 allowed us to create and modify servers far quicker and easier than ever before.

Layer 3 is where we get our hands dirty. The Software Defined Data Centre(SDDC). From here, we create our cloud accounts and start building stuff. This is accessed via a web GUI, command line tools, APIs or other platforms and integrations. This is essentially a management layer, not a workload layer, in that it allows us to govern our resources, control access, manage costs, security, scale, redundancy and availability. It is here that “infrastructure as code” becomes a reality.

Layer 4. The Native Service (such as S3, Lambda, or RDS) or machine instance (such as EC2) layer. This is where we create actual workloads, store data, process information and make things happen. At this level, we could create an instance inside a VPC, set up the security groups and NACLs, and provide access to a developer or administrator via RDP, SSH, or other protocol. At this layer, humans that require access don’t need Layer 3 (SDDC) access in order to do their job. In many ways, this is the actual IaaS (Infrastructure as a Service) layer.

Layer 5. I’m not convinced this is all that different to layer 4, but it’s useful to distinguish it for the purpose of defining *who* has access. This layer is analogous to layer 7 of the OSI, that is, it’s end-user-facing, such as the front end of a web application, the interactions taking place on a mobile app, or the connectivity to IoT devices. Potentially, this is also analogous to SaaS (Software as a Service), if you consider it from the user’s perspective. Layer 5 applications exist as a function of the full stack underneath it – the physical resources in datacentres, the hypervisor, the management layer, virtual machines and services, and the code that runs on or interacts with the services.

Whether something like an OSI model for cloud becomes adopted or not, we’re beginning to transition into a new realm of terminology, and the old definitions no longer apply.

I hope you found this useful, and I’d love to hear your feedback and improvements on this model. Take a look at ISO/IEC 17788 if you’d like to read more about cloud computing terms and definitions.

Finally, if you’d like me to speak and present at your event or your business, or provide consultation and advice, please get in touch.

Tom@tomgeraghty.co.uk

@tomgeraghty

https://www.linkedin.com/in/geraghtytom/